What Does "Retro" Mean in 2026?

While the term retro game is thrown around a lot, it's surprisingly hard to define.

Welcome to the inaugural newsletter of Remastered! I recommend checking out my about page for a more detailed breakdown of who I am and what I’m planning to do with this newsletter. For now, the newsletter will remain free, but you can find a link to my Ko-fi if you’d like to support me. To kick things off, I’m revisiting what “retro gaming” really means in 2026.

Defining “Retro” Isn’t As Simple As You Think

In a 2024 Save State article, I determined that the definition of “retro” video game is constantly evolving. While those of us who remember the golden age of the Angry Video Game Nerd and the rise of 8-bit-inspired indies like Shovel Knight tend to peg that term to games from the NES or even earlier, the reality is that games from the 2000s are now just as old as several “retro” titles were then.

Since I wrote that Save State article, the Nintendo DS and Xbox 360 both turned twenty, with the PS3 and Wii’s 20-year anniversaries quickly approaching. If you consider anything over two decades old “retro”, consoles that feel more recent are starting to fit that definition. I want to respect that reality as I set out on this journey to revive some concepts from Save State into this Remastered newsletter.

It also has me thinking about how terms like “retro” and “classic” and “nostalgia” are so haphazardly tossed around in video game spaces. Something like the original Super Mario Bros. is obviously retro, but Shovel Knight can also feel “retro” from a design and aesthetic standpoint. We're reaching Inception levels of complexity when you refer to a game with that terminology nowadays.

That’s one of the reasons why we have a hard time differentiating between remasters and remakes, and it’s also why I don’t want this newsletter to be solely focused on the past. In 2026, “retro” is as much of a feeling as it is a descriptor of time.

As part of my academic studies at Old Dominion University, I read a Media and Communication article by Tim Wulf and several other authors that argues retro games have experienced such success because they serve as a “psychological resource for the players’ sense of self and well-being.” Playing a simpler, older game with some rough edges reminds us of a simpler time in life, when we may have also had more rough edges.

While the term “retro game” originally applied to titles released in a certain era, it has since become almost synonymous with “games that make me feel nostalgic when I play them.” Most often, that comes from literally playing an older game. I still revisit some of the Xbox and Game Boy games from my youth, which is proof that what’s considered “retro” shifts from person to person.

Sometimes, those feelings can come from more recently released games. "Retro" now also refers to a visual aesthetic and game design approach. When I hear that a new indie game is “retro-inspired”, I assume it has a visual style somewhere between the Atari 2600 and PS1, and that it will be a bit obtuse and difficult but ultimately rewarding.

This happens because we like to romanticize older games. Frank Bosman specifically wrote about this subject for an academic article titled Video Game Romanticism, highlighting how game developers and players like to idealize the past and realize that in what they play. This excerpt breaks that down succinctly:

Video game Romanticism, as an application of the general understanding of Romanticism to the field of video games, is the idealization of the past, presumed technologically inferior but culturally, socially and/or spiritually superior to our time, by means of video games. This idealization or romanticization of video games can take one of two concrete shapes: video games can be the subject of this romanticization, when games are the means by which the idealization of the past is realized, or they can be the object of romanticization.

The Romanticism of video games directly aligned with the rise in popularity of retro games and newer games taking on a retro aesthetic. It’s why we treasure gaming classics so much. However, it also creates complications when a game is remade to be more modern.

Dragon Quest VII Reimagined (Square Enix)

Take Dragon Quest VII, first released on PS1 in Japan in 2000. Its recent re-release earned the subtitle “Reimagined” with its drastic overhaul of the look, name, and feel of the experience. Square Enix outright promoted how they modernized the experience by streamlining it, suggesting that retro games have a clunkier and more obtuse nature.

Dragon Quest VII Reimagined’s approach to perceived “modernization” has proven controversial. Its perceived flaws are seen by fans as part of the core experience. Adam Vitale’s RPG Site review most clearly lays out this perspective: “Dragon Quest VII Reimagined still encapsulates much of what makes Dragon Quest VII resonant, but with every possible edge sanded off. It succeeds at streamlining a lengthy adventure at the expense of player discovery and friction.”

As players, we romanticize the friction in older games. Meanwhile, some game developers see that as a dated concession that can be solved in a remake. A game becomes “retro” when it directly intertwines with our nostalgia for video game history, while more modern games build on those feelings and design choices to create something that feels retro-adjacent.

That’s one of the reasons why it’s so hard to outright define the term “retro game”, and so important for retro enthusiasts to consider the entire history of the video game medium, including what’s coming out right now. There’s no shortage of new games building on players’ nostalgia for games released over a decade ago. We’re already seeing Gen Alpha nostalgia for legacy modes like Fortnite OG in the live service titles that still dominate gaming today.

The definition of retro ultimately lies in the eye of the beholder, and its definition continues to evolve so quickly that it’ll be hard to truly refine or restrict it to a certain time period. Maybe Mike Mika, CEO of Atari 50 developer Digital Eclipse, was onto something in 2024 when they told me they don’t use the words retro or classic at all in their work. In 2026, Retro is a historical demarcation, an aesthetic, and an approach to game design. I want this newsletter to cover all of that.

This is my long-winded way of saying that I don’t plan on restricting what this newsletter can cover. Stories connected to games and events in the industry 20+ years ago will be of particular interest, of course, but if the story of a more recently-released game catches my eye, I will still cover it if I feel like there’s a connection to the ever-evolving nature of retro gaming.

It's important to reflect on the video game industry's past as we chart its future. By understanding the struggles, successes, and impacts of older games, "retro" or not, we can better tackle the challenges we're facing today. What's retro is new again, or maybe the definition of retro was never quite right to begin with.

What's Old Is News Again

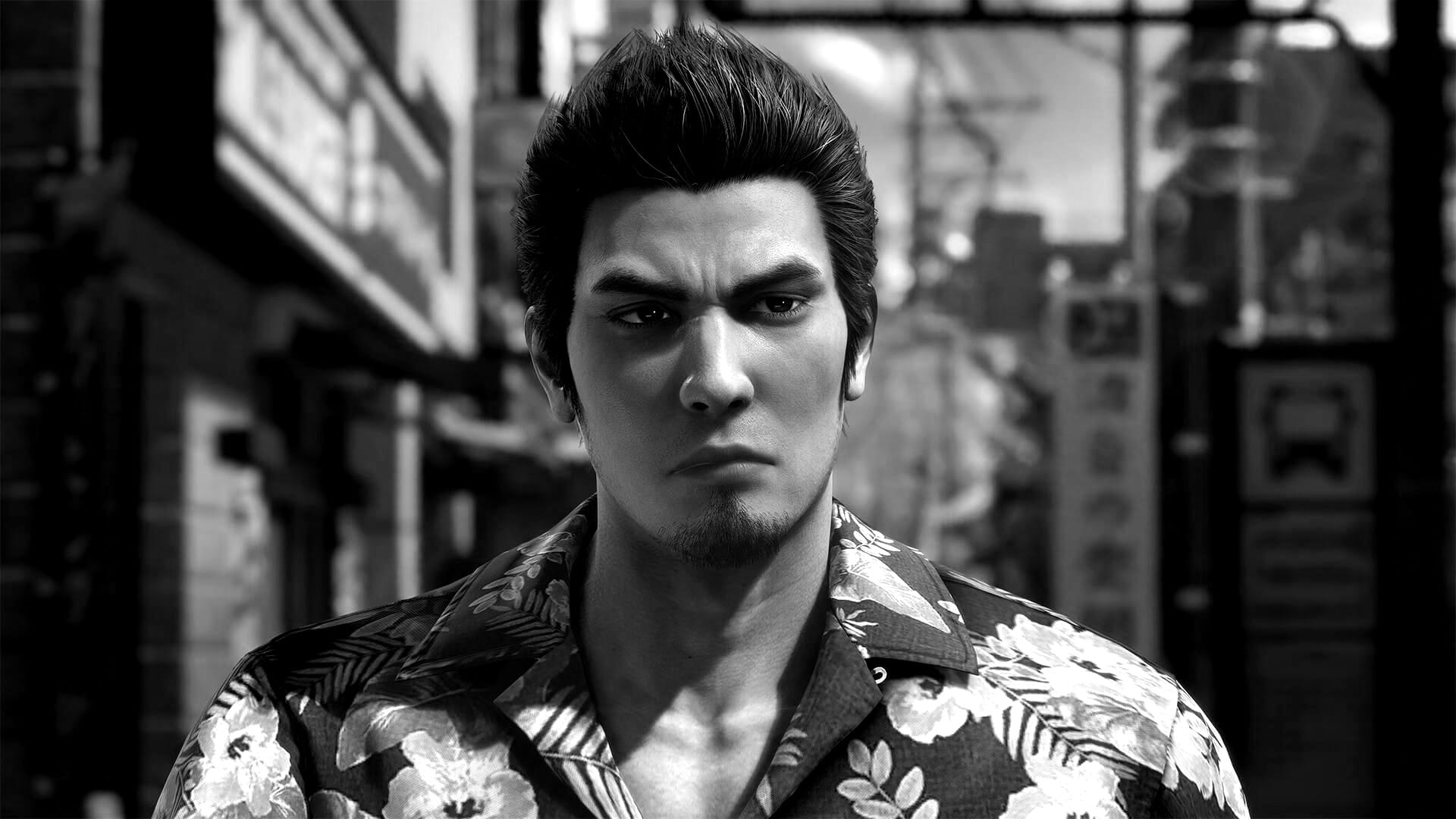

A Nintendo Direct Partner Showcase, Yakuza Kiwami 3, Lovish, and more

- A Nintendo Direct Partner Showcase featured some retro-focused announcements:

- HD-2D game The Adventures of Elliot: The Millennium Tales received a June 18 release date. This is my most anticipated game of the year, and I can’t wait to play more of it.

- The Super Bomberman Collection was shadow-dropped by Konami in North America. A collection of Goemon games isn't getting released in the US.

- Hamster kicked off a Console Archives line of games on Switch. This opens up the eShop to more PlayStation ports, with the first one being Cool Boarders.

- The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Remastered comes to Switch 2 later this year, although indie RPG Dread Delusion will come to Nintendo's console before that. A good year for fans of old-school Elder Scrolls.

- Game Informer published an Oral History of Fallout that serves as a fascinating breakdown of one of the industry’s most iconic RPG series.

- I wrote about Unravel for GameSpot to celebrate its tenth anniversary. There’s not much in the way of “news” in it, but it’s a powerful story about why passion and love are the secret sauce behind great games.

- Yakuza 3 Kiwami & Dark Ties launched to mixed reviews, with the controversial casting of Teruyuki Kagawa drawing particular criticism.

The are the games that have captured my attention recently:

- Lovish: A tough but hilarious meta-platformer from the creator of Astalon: Tears of the Earth. I haven’t seen much discussion about this game, but it’s currently my favorite game of the year. I recommend reading Noisy Pixel’s review of Lovish.

- Hermit and Pig: An Earthbound-inspired adventure not trying to be like Undertale. I’ve had my eye on this game for years, and I’m glad it lived up to expectations.

- Romeo is a Dead Man: A new SUDA51 game release always demands attention. This one’s a charming ode to all different kinds of art forms and aesthetics, including retro ones.

- Terrinoth: Heroes of Descent: I previewed the first-ever video game in Fantasy Flight Games’ long-running tabletop universe for GameSpot.

The Games We Played

Star Wars Battlefront II (2005)

For the first-ever The Games We Played, I want to discuss my favorite game of all time: Star Wars Battlefront II. No, not the 2017 game mired in controversy before making a miraculous recovery in popularity. I’m referring to the 2005 game from Pandemic Studios that, to this day, remains perhaps the greatest sandbox ever bestowed upon Star Wars fans. I’m so glad I caught a TV commercial for this game at a pizza place on the South Side of Chicago, long since closed, and asked my parents for it for Christmas.

It’s the game I have the most fond childhood memories of playing, my quintessential gaming experience that made me fall in love with the art form. I’d never tried a Battlefield-type game before, so Battlefront II’s vast scale and command post-based warfare felt fresh and awe-inspiring to me. I’d create my own storyline and rewrite Star Wars history in its Instant Action mode, alone and with my brother, or I’d fill in the blanks as I played through a strategic Galactic Conquest campaign.

Its campaign isn’t too shabby either, at least when it comes to the parts narrated by Temuera Morrison. Star Wars Battlefront II cemented my fandom of both Star Wars and the video game industry. At this point, I might as well consider it retro because of its age (over 20 years old!) and its ability to elicit those feelings of nostalgia and romanticism in me.

I doubt Star Wars Battlefront II will ever be dethroned as my favorite game of all time. Emotionally, it’s unlikely any new game will be able to match that feeling. Still, it gives me reason to look forward to new Star Wars games and multiplayer shooters. I can play them to see if they recapture any bit of that magic. Star Wars Battlefront II changed my life.

Thanks to Myles McNutt and Francesco Franzese for their help with editing this first edition of Remastered, and thank you all for reading all the way through the inaugural Remastered newsletter. Expect a newsletter every Friday over the coming weeks! While I plan on keeping Remastered free for the time being, consider supporting me through Ko-Fi!